Projects often start with meetings. Often, beautiful meetings lead to beautiful projects too though it must be said, this is hardly a rule.

I met Teru Yanagihara in 2015, during a short stay in Kyoto on the occasion of my first solo show in Japan, “Atmosfera”, at the Sfera Exhibition venue in the Kyoto city centre.

At that time, Teru had set up his studio in a gorgeous house located on the edge of Kyoto, in the Northern neighbourhood of Kitayama.

The house was at the foot of a hill full of lush vegetation. It was a house laden with history and this history was partly told to me, though I haven’t got a clear enough memory of it to retell it here.

Along with the beauty and serenity of the place, the quality of the meeting with Teru and his team would mark a happy starting point for this unhoped-for project. Teru suggested that I design the third collection for the young 1616 Arita Japan brand, of which he was, and still is, Art Director.

I was immediately delighted that he asked. Not only because of my interest in the project itself — designing a whole collection of table objects in porcelain — but also because it would allow me to prolong and deepen the relationship I had begun with Japan in 2012, during my four-month residency in Villa Kujuyama (Kyoto).

Only the following year, in October 2016, did I go to Arita, on the invitation of the project’s initiator and investor, Noriyuki Momota.

I visited a great number of production workshops, immersing myself in the peculiar atmosphere of Artia, which has been entirely centred on the production of porcelain since the 17th Century — 1616 precisely, the year in which, as legend has it, a Korean potter found a kaolin deposit in Arita. A vast production encompasses everything from the manufacturing of raw material to the manufacturing of finished objects — and all sorts of objects, from the most common to the most unbelievably sophisticated.

It went without saying that the third collection had to distinguish itself from the previous two. After Teru’s proposition — centred on the standard and its infinity of possible adaptations — and that of Sholten & Baijings — centred on the form-colour-surface relationship — I decided to concentrate my project on the form-decoration connection.

The challenge then became to design the object’s shape and decoration together, as opposed to designing first the shape and later the decoration.

Be it a plate, a platter or a bowl, and beyond the functional specifics of each, one of the unavoidable questions that arises during the design process is that of the container’s limit and therefore the design of the container’s edge — the edge that defines where the container begins and ends, and so, the object itself.

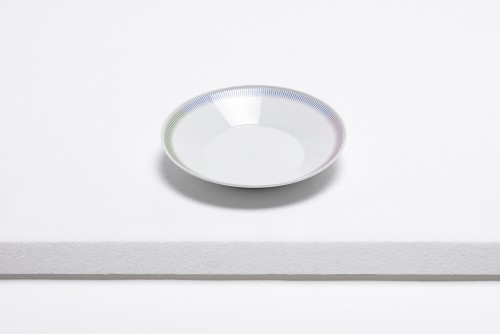

As I designed the object in its entirety, I paid special attention to the design of the edge so as to make it the collection’s special feature.

I opted for a simple detail, a small “bulge” along the edge of the object, from which the motif of gradual shading would emanate. The motif quickly becomes subdued towards the centre of the object, thus creating a zone of pure whiteness — that of enamelled porcelain — a zone which offers itself as an immaculate recipient willing to welcome and enhance any dish.

As I write this text, I’m receiving the first production pieces from Japan after two years of development, and looking at them I remember everything I have recounted above. It all started in the house on the edge of Kyoto. But is it by chance then, by pure coincidence, that the collection’s very singularity is held in a detail located at the edge of the object?

That’s something worth pondering.

Thinking about it, it is as if subconsciously I wanted to evoke the genesis of the project in the object’s very design.

In parallel to the collection, we later added a series of six large platters, whose hand-painted decoration — a variation on an “arabesques” drawing — is placed at the centre of the object.

The wealth of know-how in Arita is such that it would have been a shame to deny oneself the skills of the craftsmen who paint decorations: they managed to reproduce my drawings, as if, almost 10 000 km away, their hands became extensions of my own for a while.

Arita: so far, so near!

Pierre Charpin, Septembre 2018

Les projets commencent souvent par des rencontres. Souvent aussi, les belles rencontres donnent naissance à de beaux projets, même si c’est loin d’être toujours le cas, faut il en convenir.

J’ai rencontré Teru Yanagihara en octobre 2015 alors que j’effectuais un petit séjour à Kyoto à l’occasion de ma première exposition personnelle au Japon, « Atmosfera », qui se tenait à l’espace Sfera Exhibition au centre de Kyoto.

A ce moment là, Teru avait installé son atelier dans une très belle maison située à la lisère de la ville dans le quartier nord nommé Kitayama. La maison affleurait la colline et sa végétation luxuriante. C’était une maison chargée d’histoire, elle m’a été en partie racontée, mais je ne l’ai pas suffisamment mémorisée pour pouvoir ici la raconter.

La qualité de la rencontre avec Teru et son équipe conjuguée à la beauté et à la sérénité qui se dégageait du lieu allait marquer l’heureux point de départ de ce projet inespéré. Teru me proposait de dessiner la troisième collection pour la jeune marque 1616 Arita Japan, dont il assurait et assure encore aujourd’hui la direction artistique.

Je me réjouissais immédiatement de sa proposition. Non seulement pour l’intérêt du projet lui même, dessiner toute une collection d’objets pour la table en porcelaine, mais aussi pour le fait qu’il me permettait de faire perdurer et d’approfondir la relation que j’avais initié avec le Japon en 2012 lors de ma résidence de 4 mois à la Villa Kujuyama (Kyoto).

Ce n’est que l’année suivante en octobre 2016, à l’invitation de Noriyuki Momota, l’instigateur et investisseur du projet que je me rendais à Arita.

Je visitais alors un grand nombre d’ateliers de production et m’imprégnais de l’atmosphère particulière de la ville totalement centrée sur la production de céramique depuis le 17eme siècle, 1616 exactement, l’année ou selon la légende un potier Coréen y découvrit un gisement de Kaolin. Une vaste production allant de la fabrication de la matière première à la fabrication d’objets finis, objets en tout genre, du plus commun au plus incroyablement sophistiqué.

Il allait de soi que cette troisième collection devait se distinguer des deux précédentes. Après la proposition de Teru centrée sur le standard et de ses infinis possibles déclinaisons et celle de Sholten & Baijings centrée sur la relation forme couleur surface, je décidais d’orienter mon projet autour du rapport forme décor.

L’enjeu devenait dès lors de dessiner conjointement la forme d’un objet et son décor et non la forme puis un décor.

Qu’il s’agisse d’une assiette, d’un plat, d’un bol, au delà des spécificités fonctionnelles propres à chacun, une des questions incontournables posée par leur dessin est celle de la limite du contenant, donc du dessin de son contour, contour qui définit où commence, ou où finit le contenant, c’est à dire l’objet lui même.

Tout en dessinant la totalité de l’objet, je portais une attention particulière au dessin de ce contour afin d’en faire le signe distinctif de cette collection.

J’optais pour un simple détail, un petit ‘’bourrelet’’ à la lisière de l’objet contre lequel allait se caler le motif en dégradé. Motif qui se dégrade rapidement vers le centre de l’objet créant ainsi une zone de pure blancheur, celle de la porcelaine émaillée, zone qui s’offre comme réceptacle immaculé prêt à accueillir et valoriser n’importe quel mets.

Alors que j’écris ce texte au moment même où je reçois du Japon, après deux années de développement, les premières pièces de production, les regardant, il m’est revenu à l’esprit ce que je viens de relater plus haut. C’est dans cette maison située à la lisière de la ville de Kyoto que tout cela a commencé. Mais alors, est ce un hasard, une pure coïncidence si toute la singularité de cette collection tient dans un détail qui se situe à la lisière de l’objet?

Voilà un fait qui mérite d’être questionné.

A y repenser, c’est comme si j’avais de manière inconsciente, voulu évoqué dans le dessin même de l’objet la genèse de ce projet.

Parallèlement à cette collection, nous avons dans un second temps ajouté une série de six grands plats, dont le décor peint à la main, une variation de dessin en « arabesques », prend cette fois ci place au centre de l’objet.

L’étendue des savoirs faire est si grande à Arita, qu’il aurait été dommage de se priver de l’habileté des artisans qui peignent les décors et qui n’ont pas failli dans la reproduction de mes dessins, comme si leurs mains devenaient pour un temps, et ce a presque 10 000 km de distance, l’extension de mes propres mains.

Arita : si loin, si près!

Pierre Charpin, septembre 2018