The World at thirty centimeters from the Floor.

Published in “Quali Cose Siamo”,

Triennale Design Museum exhibition catalogue, Electra edition.

It was late afternoon on a cold January day when

I received a laconic e-mail from Alessandro Mendini: “Dear Pierre, as soon as you read this e-mail, can you call me on my cell phone? Thanks a million!”

A few minutes later I was talking with Alessandro,who told me: “I was thinking about something that might be interesting. You know,

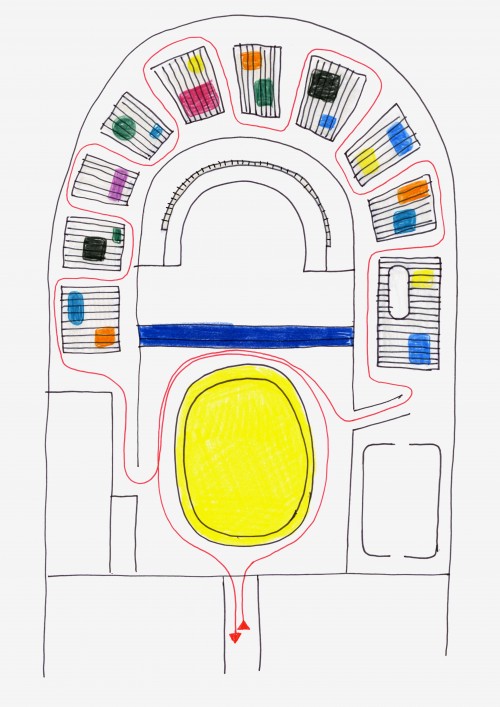

I’m going to be the curator for the third edition of the Triennale Design Museum. I thought you would be the right person to plan the scenography. I’d like something simple, not sophisticated, something precise, something fresh. You think you’d be interested?”After receiving a few indications about the content, I said yes, I was interested in the project, and that I felt very honored at his proposal. Alessandro made it clear right away that it wasn’t yet certain, that he had to run the idea by the people managing the Triennale, and that, in the end, it was their decision. He made it clear that it would all have to be done in a big hurry: “the museum inauguration is on 26 March, at 6 pm.”

The next day, Silvana Annicchiarico called me to tell me that she was very happy, as museum director,

to entrust me with the project for the scenography for the new edition.

There is no doubt about the fact that my history has been significantly marked by the passionate relationship I have always had with Italian Design and with Milan, its capital.

It started out from my discovery, in the early 1980s, of Italian Design and its dominant figures (the so-called Masters), as well as of the theories and practices of the groups—of Counter Design, Radical Design, Post Radical—that I started shifting gradually—I was a student at the fine arts school

at the time—from the field of plastic arts to that

of design.

It seemed to me that the values Italian Design brought along with itself were strictly and indissolubly interwoven with humanistic and aesthetic concerns. Design revealed itself to me as an actual means of expression. At the same time I also discovered a practice that is open and free, not merely pragmatic, and sometimes closer to the universe of art than to that of design: the performance, the installation, the criticism, the irony, the theory, the manifesto…

Here I found an almost natural affinity with my sensitivity, some possible answers to my questions

as a young adult in search of an artistic practice,

of an aesthetic expression capable of establishing ties with life that are more direct, more concrete.

In this encounter with Italian Design I found that opening that each of us was seeking, as students

at the school of fine arts, in the face of that closure then represented by conceptual art and minimal art (which, besides, have profoundly influenced me), as well as by everything else that at the time we labeled as “art for the sake of art.”

For this reason, I have always considered design, above all, as “an Italian matter,” and Italian as its natural language, to the point that, when I think about certain things on the subject, it often happens that my thoughts occur to me in Italian.

Italian Design exerted a great force of attraction beyond its frontiers, and it seemed to be endowed with a faculty of assimilation (Sapper, Sowden…) and with a capacity of regenerating itself owing to contributions from without (Starck, Morrison…). Itsstructure, or perhaps, actually, its non-structure, revealed itself as being the most appropriate and the most inventive for facing our world and its incessant movement.

This passionate, affective relationship with Italian Design has also, paradoxically, been constructed upon a distance I have always maintained. I have never made the decision of moving to the “promised land-city,” nor of going to live in the house of the “gods.” In effect, I have always kept myself away from divine protections, even if, through the course of the years, I have cultivated affinities and established complicities.

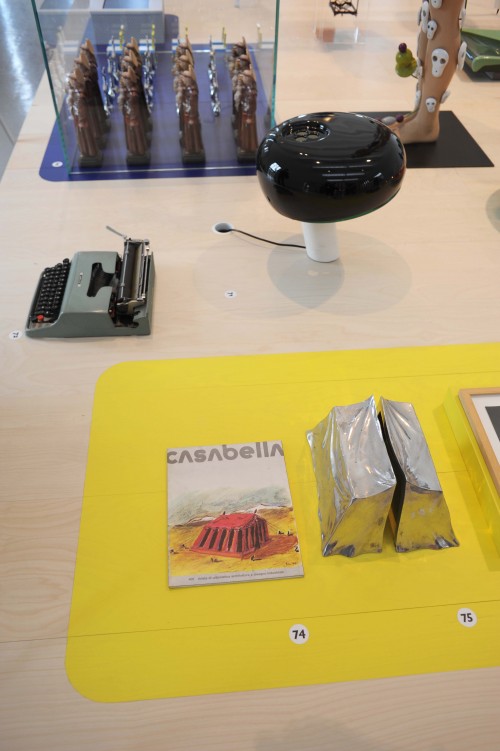

The first time I saw the images for the works selected for the museum, I had the strange sensation I was undertaking a journey, or of finding myself

in the position of an explorer, invited to scrutinize the contents of a mind (that of Alessandro? or of

a country?) whose memory, disjointed by time, had produced a great quantity and variety of information, images, sensations.

This memory was restored to me, without hierarchy, without chronological or typological classification. It was only the opening of my spirit, my curiosity, my memory, and my sensitivity that would allow me to cope and, at times, to make sense out of this vast profusion.

I think back on one of Alessandro’s considerations, somewhat sardonic—he knows very well how to make them in such circumstances—that came once to break up the “scholarly” atmosphere of one of our work meetings: “In the end, is anybody going to understand anything out of all this?” Probably, though, it’s not a question of understanding “something.” It’s probably just a matter of letting oneself be transported by one’s own sensations, by one’s own inspirations and questions, of wandering, of roaming, through these Things We Are.

That’s what I’ve tried to stage.

Pierre Charpin, March 2010

Le monde à trente centimètre du sol.

Publié dans “Quali Cose Siamo”,

Catalogue d’exposition à la Triennale Design Museum, Electra edition.

C’est en toute fin d’après-midi d’une froide journée de la mi-janvier qu’est arrivé un mail laconique d’Alessandro Mendini: Cher Pierre, dès que tu liras ce mail, pourrais-tu m’appeler sur mon portable. Mille mercis.

Quelques instants plus tard je conversais avec Alessandro qui me disait : « J’ai pensé à une chose qui pourrait être intéressante. Tu sais que je suis le curateur de la troisième version du musée du design de la Triennale et j’ai pensé que tu étais la personne adéquate pour en faire la scénographie. Je voudrais quelque chose de simple, de non-sophistiqué, de précis, quelque chose de frais. Est-ce que tu penses que cela pourrait t’intéresser ?».

Après qu’il m’ait donné quelques indications sur le contenu, j’ai répondu que oui et que je me sentais très honoré qu’il ait pensé à moi pour ce projet. Alessandro a tout de suite précisé qu’il n’y avait encore rien de sûr, qu’il devait soumettre l’idée aux responsables de la Triennale, et qu’en dernière instance, ce serait eux qui décideraient. Il a aussi précisé que tout devait se faire très vite, « le musée s’inaugure le 26 mars à 18h ».

Le Lendemain, Silvana Annicchiarico m’appelait pour me dire qu’elle était très contente de me confier, en tant que directrice du musée, le projet de scénographie de la nouvelle version du musée.

Il ne fait aucun doute que mon histoire à été fortement marqué par le rapport passionné que j’ai toujours entretenu avec le design Italien, et Milan, qui en est sa capitale.

C’est par ma découverte au tout début des années quatre-vingt, du design Italien et de ses figures dominantes, les bien nommés « Maestri », comme de l’ensemble des théories et des pratiques des groupes du Contre Design, du Design Radical et Post Radical, qu’étudiant à l’école des beaux-arts, je me suis petit à petit détourné du champ des arts plastiques, pour m’orienter vers celui du design.

Les valeurs que portait le design Italien me semblaient relever d’une imbrication étroite et indissociable entre des préoccupations clairement humanistes et esthétiques. Le design se révélait comme domaine d’expression à part entière.

J’y découvrais aussi l’exercice d’une pratique très ouverte, libre, pas seulement pragmatique, qui se rapprochait parfois fortement de formes qui appartiennent davantage au champ de l’art plutôt qu’à celui du design, comme la performance, l’installation, la critique, l’ironie, la théorie, le manifeste…

Je trouvais là les éléments d’une affinité quasi naturelle avec ma propre sensibilité, des éléments de réponses à mes questionnements de jeune adulte à la recherche d’une pratique artistique, d’une expression esthétique susceptibles d’établir des liens plus directs, plus concrets avec la vie.

Par cette rencontre avec le design Italien, je trouvais l’ouverture que chacun d’entre nous, étudiants à l’école des beaux-arts, cherchions face aux impasses que représentaient alors l’art conceptuel, l’art minimal (qui m’ont cependant fortement influencé), et tout ce que nous mettions sous l’étiquette de l’art pour l’art.

Ainsi, j’ai toujours considéré le design comme étant avant tout une affaire Italienne, et l’Italien comme la langue naturelle du design, au point que quand je pense à certaines choses qui le concernent, il m’arrive que ces pensées me viennent en Italien.

Le design Italien rayonnait bien au-delà de son propre territoire. Il exerçait une force d’attraction et semblait doté d’une faculté à assimiler (Sapper, Sowden…) et à se régénérer par les apports extérieurs (Starck, Morrison…). Sa structure où peut-être même sa non structure, se révélait la plus adéquate et la plus inventive pour appréhender notre monde définitivement mouvant.

Ce rapport passionné, affectif même, avec le design Italien, c’est aussi paradoxalement construit sur une distance que j’ai toujours volontairement maintenue. Je n’ai jamais pris la décision de m’expatrier vers la « terre /ville promise », jamais pris la décision d’habiter la maison des « dieux ». De fait, je me suis toujours maintenu à l’écart des protections « divines », quand bien même j’ai cultivé certaines affinités, certaines complicités.

Quand pour la première fois il m’a été présenté sous forme d’images, l’ensemble des objets et des oeuvres sélectionnés pour le musée, j’ai eu l’étrange impression d’entreprendre un voyage, ou de me retrouver dans la position d’un explorateur, invité à scruter le contenu d’un cerveau (celui d’Alessandro, celui d’une nation ?) dont la mémoire aurait engrangé au fil du temps, une grande quantité, une grande variété d’informations, d’images, de sensations.

Cette mémoire m’était restituée sans hiérarchie, sans discernement, sans classification, ni chronologique, ni typologique… Seule ma disponibilité d’esprit, ma curiosité, ma mémoire et ma propre sensibilité me permettaient de naviguer et parfois même de me repérer à l’Intérieur de cette profusion.

Je me souviens d’une réflexion quelque peu amusée, dont Alessandro a la parfaite maîtrise, pour venir tempérer l’une de nos studieuses séances de travail : « Est-ce que quelqu’un va comprendre quelque chose dans tout cela ? ».

Mais y a-t-il quelque chose à comprendre ? Au fond, il n’y a peut-être qu’à se laisser prendre par ses propres sensations, par ses propres inspirations, ses interrogations, se laisser aller à sa propre divagation, à son errance parmi les choses que nous sommes.

Voilà ce que j’ai tenté de scénographier.

Pierre Charpin, Mars 2010